Can I just say that this was such a nice project to take on? Seriously. For one, I am sure that there are walls that I wouldn’t run through for Mistress Camille, but I have yet to find them. Second, it was a quick turn around piece I couldn’t linger on too long. And lastly, but oh so very importantly, I felt like I got back into doing the art that I started doing from the very beginning of my journey. This piece allowed me to digest a piece of extant art, really get inside of it, and then like a Skywalker on Hoth, carve it open, crawl into its belly, and get comfortable. I haven’t retired, but I definitely had to take a break from the pace that I was doing even a year or two ago. But come now, I have been a little busy! Ye Olde Wordfactory was just down for a little maintenance, but the owners are anxious to get the presses pumping again, just maybe at a slightly more measured pace. You know, just like me. Measured. Heh.

Given my approach, it is always so nice when you find the perfect piece to use as a basis. So when I received the assignment that described the recipient’s persona as late period, Portuguese, and a frequent traveler to India… well, I just knew that there had to be something that would fit the bill. Thus, we find Luís de Camões, a Portuguese poet from the 16th Century, who served in the Royal Navy and was stationed in India… sort of. He would have totally been stationed in India, if he hadn’t picked a fight with someone in a street festival, and “wounded them with his blade”. He did eventually make it to India, but his enlistment was… slightly less voluntary. He quoted Scipio Africanus on his way out, saying “Ungrateful Fatherland, you will not possess my bones.”

Perfect.

He very conveniently wrote probably one of the most important epic poems in the Portuguese language, so there’s that too. That brings us to Os Lusíadas, or The Lusiads, which I used as the model for our scroll. It’s a truly monumental work, and I am not going to dive into it in great depth here, but there is plenty written about it. Instead, I am going to apply my normal tactic to the opening stanze of “The Argument”, basically laying out the subject of the poem to come, invoking the muses, yadda yadda.

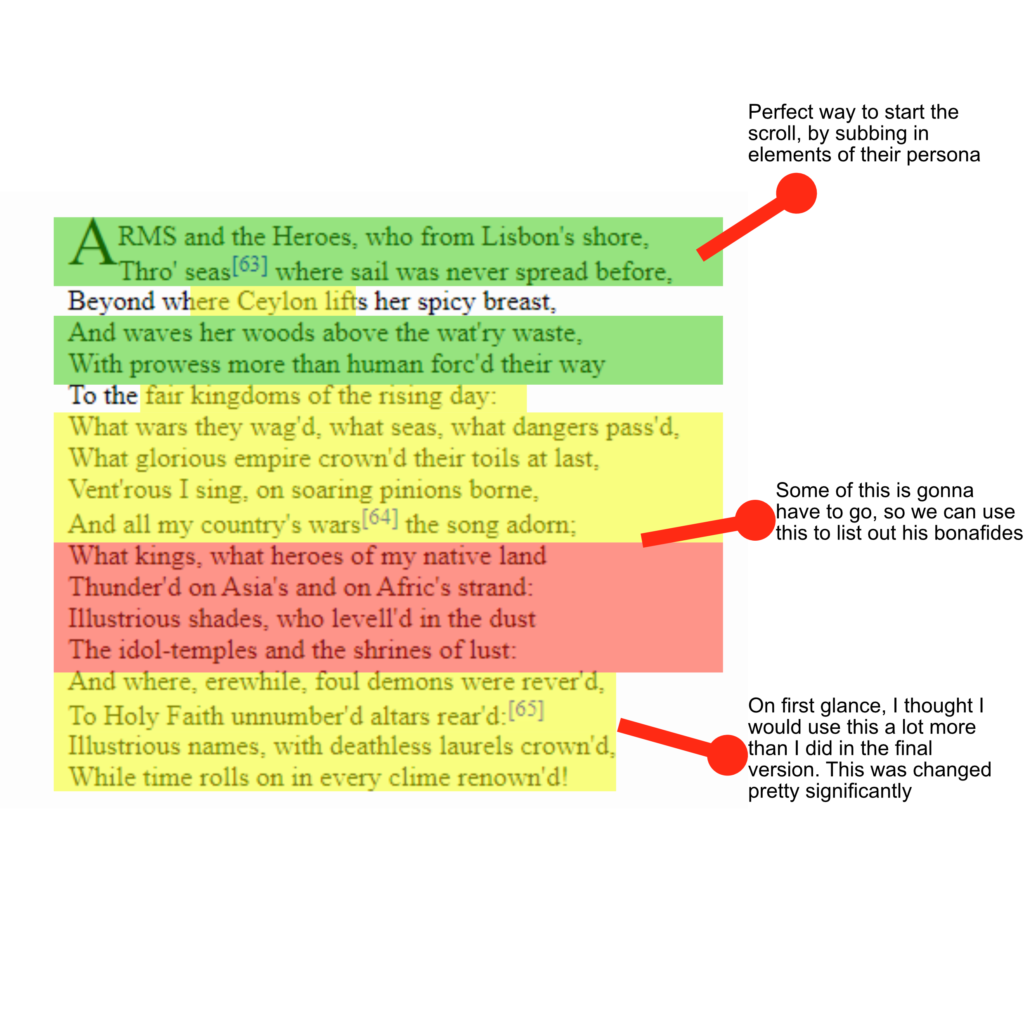

The stanza broke down pretty easily into elements that I could use almost exactly, like the ones detailing the hero of the poem as traveling, specifically by sea. I had to swap out some references, making Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) into The Barony of the Bridge, which is where the recipient is from. The middle became a little more complicated, and while I was able to lift some of the poetry directly for flavor, “Vent’rous I sing, on soaring pinions borne,” the references themselves were either too specific to the poem and not the persona or sort of unsavory. That’s all fine, because that gave me ample room to list out the bonafides of the recipient, and make some references to the last few years where this gentle in particular had served in a tremendous capacity.

When I first went through to highlight what I wanted to use, I thought the last stanza would wind up closer to the original than it became. The overt religiousity had to be moved out, but otherwise I thought I could make some subtle manipulations to get it to work for what I needed. By that point in the scroll I needed the date/time/place stuff, and I got struck by the curse that has hit me before. “Malagentia” as a word is hard to fit into iambic poetry. There, I said it. It has five syllables so it dominates either quatrameter or pentameter in a way that requires balance and precision. Sometimes I get it right, but boy oh boy did I work on those last four lines A LOT. I thought it was cheeky and fun to take “And where, erewhile…” and make it “And heirs…” because of how similar the words sounded to me, but other than the crown’d/renown’d rhyme it bore less and less similarity the more that I worked it.

And I guess that’s the important thing to remember about a method and a model, right? Sometimes things go precisely with that model and things are easy. But you can not be a blind servant to it. If you really work the model and understand its benefits and pitfalls, then you have to be willing to move away from it when it no longer serves. It’s sort of like when I was in music school studying composition. Incoming music students spend two to three years learning the rules of harmony, the practices of the past, the way that instruments work when they sound their best. And then, as a composer in the 21st century, you have to be willing to throw at least some, and probably most, of that away. Stravinsky wasn’t just famous because he was a brilliant composer, it’s because he broke the rules all the time. Why do you think that Rite of Spring caused a riot at its opening in Paris? Because the Bassoon part starts WAY TOO F#$%ING HIGH! But that was a hundred years ago, and now schoolchildren learn that solo on their lunch break.

All said that it was really good to sit down and work a piece like this again, it felt right and scholarly to research, and dust off my Portuguese (if only to use a translation as my model, but you gotta go to the OG), and feel like I was getting back to what I always loved to do. My SCAdian Art Goal ™ has always been one of translation, not of the material words but of the art itself. And that’s a tradition with deep roots in antiquity. For centuries, artists viewed themsleves as building on what came before, even if they were going in a new direction. Remembering my roots, and diving into a piece so rooted in the culture that I was writing for, had a parallelism that I wasn’t expecting at first glance, but just felt good.

And it was nice to feel good about writing again.